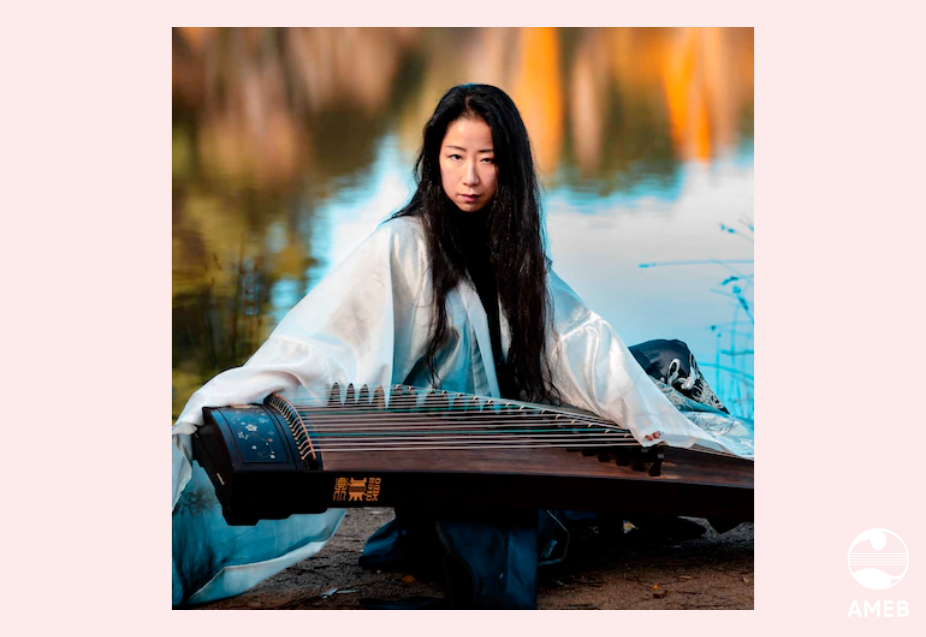

Mindy Meng Wang is a Chinese/Australian Composer and world-leading contemporary Guzheng performing artist and the first-ever musician who plays a non-western instrument to be an artist in residence at Melbourne Recital Centre. Pioneering the Guzheng (ancient Chinese harp) into many western genres, Mindy has collaborated with Australia's top musicians, including Paul Grabowsky, Deborah Cheetham, Tim Shiel, Australian Art Orchestra, Orchestra Victoria, SSO, Gorillaz and many more.

Key themes: traditional music, Western music, learning music, improvisation, identity through music.

What music were you playing growing up, and what led you to the Guzheng?

My generation was born at the beginning of the "one-child policy" in China. When the policy happened, having an educated child became very important for families because each family only had one child to continue their legacy. And that made a dramatic change in China's history.

Suddenly, all the parents wanted the best things they could give their child—education being one of those things. All the children my age and my generation were put into specialty schools to learn painting, dance, music, and other things. My parents first put me in piano class when I was five, but it didn't work. I remember my mum saying I couldn't sit still, so they thought, "that's it!" for music.

But a few years later, we had a new neighbour who happened to be the best Guzheng teacher in my region, like the entire city and province, and was quite famous in China. While she taught, I could often hear beautiful music coming out from her room in her apartment. Then I would see people go in and out of her apartment -new students going in groups, learning and coming out. I became so fascinated by the music. I remember climbing up the window to peek at what was happening inside, and I saw the instrument - so beautiful, and she's so beautiful. It gave me this amazing image of what I wanted to do. So, I went to my mum and told her, "I want this instrument," and they took me to the teacher. That's how I started.

But in China, I only played traditional music because this is a traditional instrument, and contemporary-modern music wasn't a thing.

My teacher - my neighbour- pushed my learning process even when I didn't come to her apartment for lessons. She could hear me play through the windows (especially in summer), and if I made one mistake, she would yell "stop" from inside her apartment, so I knew I had made an error. I got a lot of attention. I progressed so fast that I had to get a special accommodation to complete all the exams at sixteen. Then I received offers from one of the best conservatoriums in China and thought this would be my life: studying the Guzheng in its traditional form in the conservatorium and then teaching. But that didn't happen.

In China, you all do this one exam for college that decides your future. If you succeed and attend university, you can get a respectable job. If not, you probably have to get your own business or work in labour jobs. Everyone goes crazy preparing for the exam, but I found an English summer camp in the UK through the conservatory, and you didn't have to do anything except apply, which was much less stressful. I thought, "I'll go first and come back and work other things out". I didn't go back.

When I arrived in the UK, learning the Western approach to music was so interesting. There was so much freedom in the music. The traditional form of learning in China means repeating the same thing you're taught. Preserving tradition is a very important element of this instrument, Chinese culture, and the music that comes with it. But in England, I realised that many of my friends played one or multiple instruments and genres like pop, jazz, experiment, or classical music. I thought, "I want to stay here and try to do the same with my instruments," and that's what brought me to where I am now.

Were you improvising and experimenting with the Guzheng at the conservatorium, or was that something only started once you were in the UK?

After I arrived in the UK, I started to feel the urge to play with other people. But I didn't know how because all I knew how to play was the traditional music for my instrument. I felt like I didn't have the freedom my friends had. I wanted it, and I wanted to find it.

But, it was difficult to be free to do anything I wanted after I had spent my entire life practising for so many hours in our (Chinese) traditional way. I had lost the ability to do something different, even though I wanted it.

For two years, when I was at university in the UK, I started working on music to help me understand how it's possible to have different genres, what made music different and what music I liked—searching for what I wanted to do.

What genre of music was the first you tried to improvise on with the Guzheng?

The first try wasn't improvising. It was just playing a tune that was not traditional Chinese music. As simple as that, an already-written tune. The Guzheng is tuned to the pentatonic scale, like five notes, so the first steps felt already difficult. I started with music with pentatonic scales, and there was a strong folk music scene at the university.

I actually started it with Irish music, Irish people at home and some of my best friends there, like Irish musicians. And I love when they get together and play in the park. I go to the club, and I watch them. Everyone is playing together in a packed pub, like ten people. I thought, "wow, this is amazing!". First, I asked my friend, "how do you do that? How do you know when to do this?" They looked like they had rehearsed but had not. So, then they taught me the formula for a tune, which was the first step in trying to do something different.

What was it like playing at a pub with a group of Irish folk musicians and having a gorgeous traditional Chinese instrument?

It was fun. Guzhengs are big and not designed to move around the pubs. So, my friends helped me practice at home, but a few times, we made an effort to carry the Guzheng to the pub and play. I was so excited because I had never been part of a group playing music together like that. And I thought, "this is just the taste or hint of freedom". And I loved it.

How did you end up here in Australia, and where had the exploration and evolution of your sound transformed?

After graduating, I worked with a famous Chinese string quartet, regarded as one of the best in Europe. They played a lot of traditional music and some contemporary arrangements of traditional music. They also had the opportunity to play fun gigs, for example, with Gorillaz at an O2. Understanding how traditional, Western classical and contemporary music can come together was amazing, and I love pop. Pop helped open up my musical possibilities.

After I came to Australia, I discovered my expression in music. It became clear what I wanted to do and what I wanted to bring out. Even though I make pop, I'm still quite diverse in what I play because I still work with orchestras, Western classical, contemporary and experimental improvisation. But I also play with a team making pop-electronic music. What I play reflects my identity. When I play my instrument, it becomes an extension of my mind and my body. I don't have to think about it. It's just being.

Were there times of conflict between playing your instrument and what you wanted to explore? What did you do to get through those times?

The limitation of the instrument and the places I want to go can be a conflict. Other limitations come from the instrument's physical body—the tuning—because the Guzhung design is for one style of music, and the pentatonic scale, that limits your options. So, I'm challenged to think about getting different notes or more notes. You know, pressing the strings to bend, strain, and get to the desired pitch. Sometimes, songs have too many notes, and you have to become an octopus. I had to invent a system to find how to use the most to use notes, and make them become natural strings, sometimes, you have to combine two notes to make one. So constantly, even simple things are complex and challenging.

Also, people in the West don't know that our scores in China are a different system. Translating between our scores and Western scores is like translating into different languages. Whenever I read a Western score, I am slower at understanding it because our scores are all in numbers instead of dots. The numbers represent the distance between the note and the key (tonic) note.

Do you feel like you are developing a new tradition for Guzheng by playing and combining your sound with Western music?

What I'm doing, my practice, is giving freedom to this instrument. It is becoming an extension of my personality, which I do not want to be limited. And I want to be, you know, free. I love this instrument and want Guzheng to have the same freedom as I have. I want everyone to have that.

I encourage others, like emerging artists, to chase their claim on this instrument and be bold in doing the wrong thing. When you are the first to do something, it will always be very challenging at the beginning. But now, I can inspire others and encourage and help others to be free.